Consider the visual grammar of the "Gypsy" photograph. Exoticism, and "otherness" separating these people from their majority context. In the words of Czech Professor Miroslav Vojtĕchovský, these images are a theatre of grotesque characters, irreconcilably different, without redemption. Garish colour can further isolation.

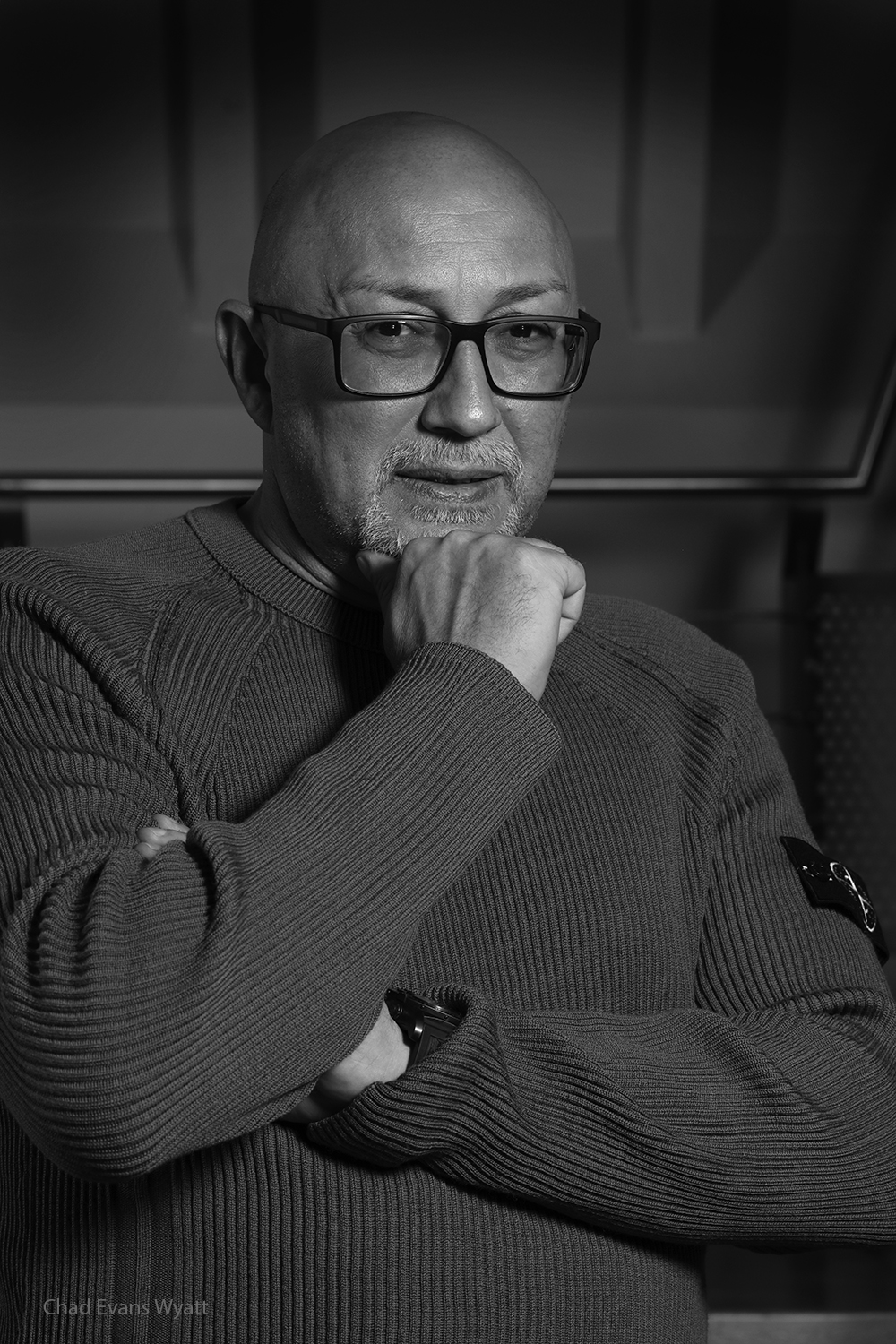

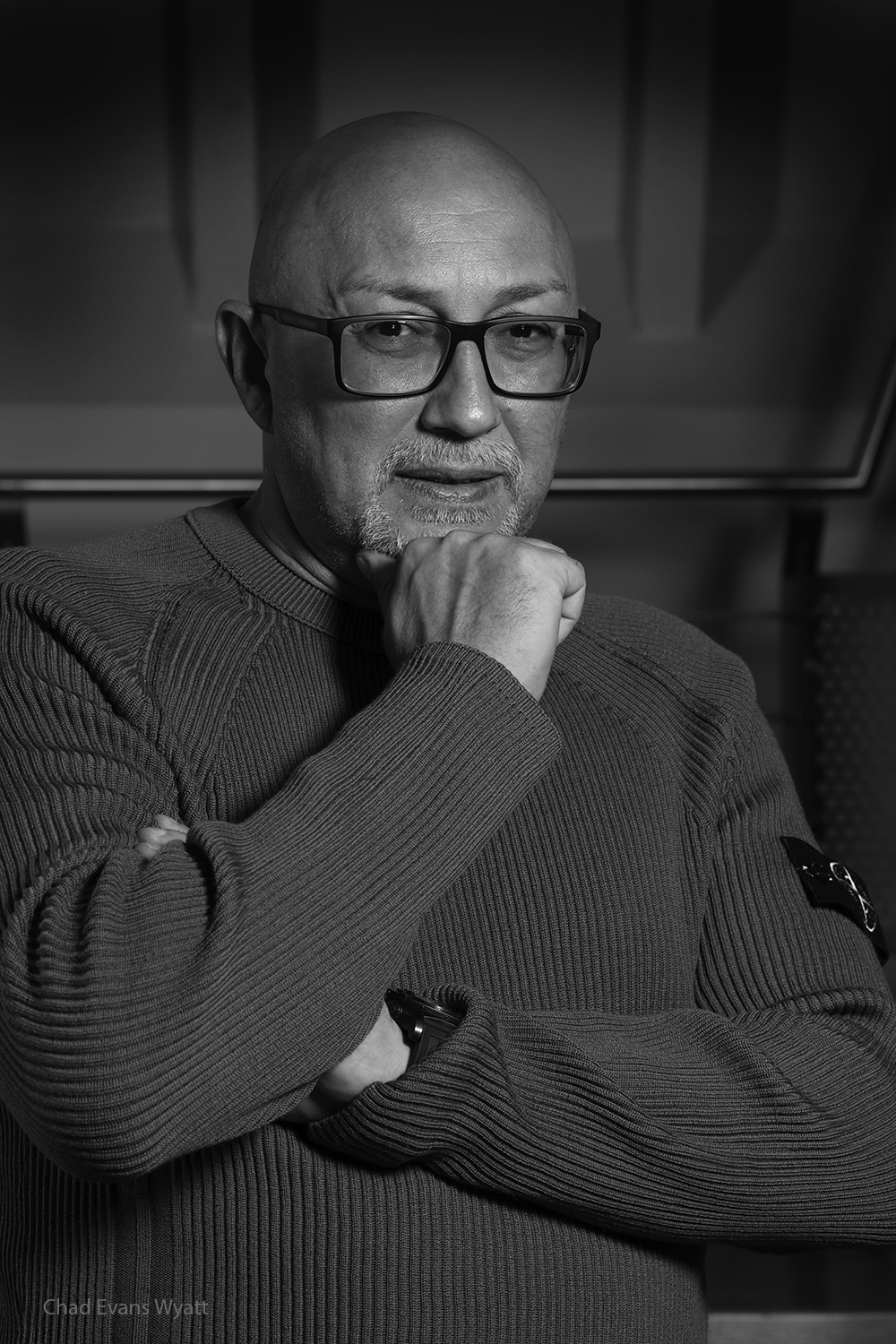

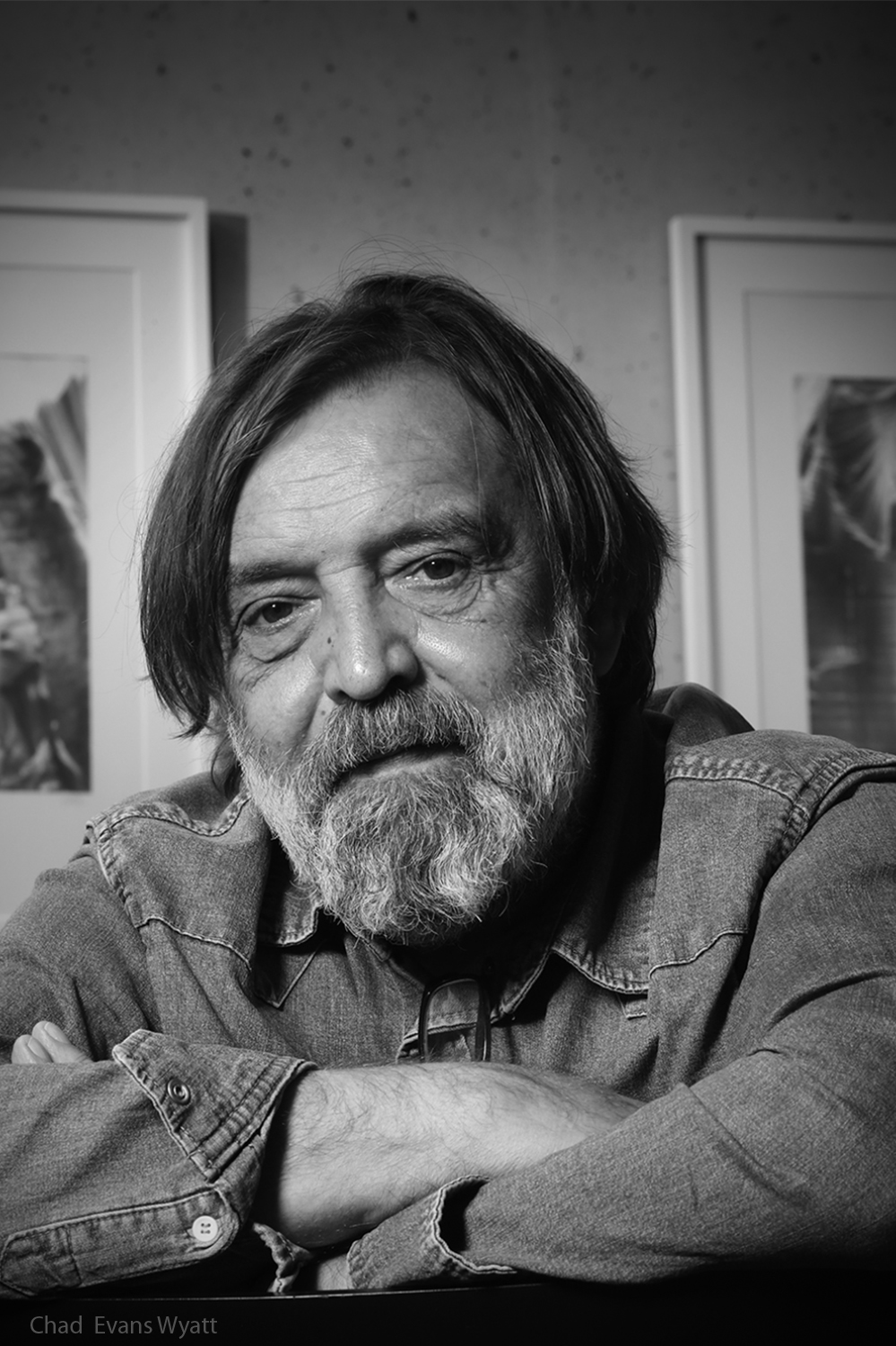

RomaRising offers respectful black and white images of dignity, countering stereotype. Many among these souls are highly educated, and have capacity to function as government ministers and lead within society. Indeed, Mr. Ciprian Necula became State Secretary in the Ministry of European Union Funds, representing the Romanian Government. He is not unique.

Mary Evelyn Porter, educator, researcher, and writer produced oral narratives starting in Bulgaria, some 200 in all. Finally the last piece fell in place: hearing each individual's formational story. These narratives obviate "the tendency to define people of colour, rather than allowing them to speak for themselves." (Alina Şerban, Actor, Romania)

Alas, some of the most prepared Roma we encountered are sequestered to the "Gypsy Bubble" of Romani Affairs. Others, unable to deploy hard-earned degrees, seek locales where they are appreciated, allowing a normal life. Witness the obvious sense of freedom on the visages of those within the Canada folio.

RomaRising became a record of feminine empowerment. Time and again we encounter women of strength and achievement stepping onto the stage, and with impact.

RomaRising also has become an international community: participants from 14 countries met one another at the RomArchive rollout in Berlin, some for the first time.

A RomaRising/EU was possible. Enthusiastic endorsement within the Roma and Sinti community was lost on European underwriting institutions. With notable exception, RomaRising is self-funded, at considerable sacrifice.

Our hope is that majority societies will come to recognise the vast talent in these individuals of RomaRising. They are found treasure within their societies. Regardless of their chosen paths, one discovers them to be superlative embodiments of our common humanity.

A note about the narratives: they are transcribed, as told to us by each participant. They are not journalism. As with the portraits, they occurred at a point in time.

We would like to mention Asen Mitkov, of Bulgaria. When introduced to us by Viktoria Petrova, we knew immediately here was the capable colleague we had always sought: a knowledgeable collaborator, who effortlessly facilitated multiple situations, be it by his spoken Romanes, his equilibrium, his empathy. Asen is at the heart of the project's final decade.

Chad Evans Wyatt and Mary Evelyn Porter

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Mario Bamberger is an art dealer and proprietor of the Kunsthandel Bamberger gallery in old town Heidelberg. "My father was an art dealer and he inspired me to go into the art business. I enjoy my profession and am glad that this is the path I chose." Ramon is married for the second time and has three children. His eldest son is thirty. His son has one daughter and works for Mercedes Benz. His middle son is also an art dealer and works at the family's other gallery in Bavaria. "I am truly proud of my family and glad I have raised my children to have both feet solidly on the ground. However, truth be told, our Yorkshire terrier secretly runs the household."

"Heidelberg is a city under glass; it does not represent the rest of Germany. It is open because it is a university city and very international."

Mario was born in Mannheim. He never knew his birth mother. His father and stepmother are Sinti and now live in Berlin. He has one brother and one sister. "Every time I tell people that I am Sinto, I get at least one stereotypical racist remark. Even close friends who seem not to be racist, have a difficult time adjusting to the fact that the Sinti are just an ethnic group like any other. The Sinti have been an integral part of German society for over six hundred years." Once Mario made a joke to his former wife's family after the two had been married for fifteen years. "Well I guess next year I'll have to start paying taxes," Mario joked. His in-laws actually believed he was being serious.

Mario's grandparents lost two children at Auschwitz. "My grandfather's brother was Jacob Bamberger, the famous boxer. He was imprisoned at Auschwitz and tortured by being given nothing to eat or drink for two weeks but saltwater. He was the only one of the family who survived Auschwitz. Jacob bore a scar on his back for the rest of his life where the Nazis had removed a kidney as part of their medical experiments on Sinti and Roma."

"My grandfather pretended to be Jewish after the war because the Jewish Holocaust came to be known, but the Sinti Holocaust was hidden. He scraped the Z (Zigeuner) off his arm and just left the number. How can it be that my grandparents' neighbour told everyone that her father was a Nazi and yet my grandfather was afraid to admit that he was Sinto."

Despite being tortured, my grandfather's brother, Jacob Bamberger was one of the first to join the Sinti Civil Rights movement. He took part in the hunger strike at the Dachau Concentration Camp in the 1980s.

"I am proud of certain talented artists whose careers I have helped to build." An upcoming exhibit at Kunsthandel Bamberger features photographs by a young Heidelberg native of the seemingly never-ending construction entitled - Heidelberg Under Construction.

Ramon_Bamberger@web.de

www.romarising.com

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Sonja Kosche is an anti-racism activist currently living in Berlin. Her Facebook effort, Antiziganismus gegen Halten (Anti-Gypsy hate speech must stop) works to document and call out examples of racist speech or actions against Sinti and Roma.

Sonja was born and raised in Germany. Her father was from the former Yugoslavia. His family were Romungro, originally from Romania. They fled to Yugoslavia during WWII when the Nazis occupied Romania. "My grandmother, Viktoria or Deka Josefina, her Roma name, was raised in a family that worked with fabrics. I loved listening to her stories of the old days."

Sonja's grandmother moved to Germany after the war because she had married a half-German man, Josef." Josef did not return from the war. Sonja wonders if her grandmother freely chose to marry him because she married at age fifteen. When there was a rumour that Josef had been located, Viktoria became depressed. Despite the fact that she was able to live a less restrictive life in Germany without the traditional values of a Romungro family, Yugoslavia was home. Neither Sonja's father nor grandmother ever really felt at home in Germany. "My father was not allowed to go to school because he did not have shoes. He was subject to racist comments by neighbours."

Sonja's mother, Elke's family operated a travelling carnival in Czechoslovakia before the war. Post war the family moved to Germany which was where her parents met.

After her grandmother died, Sonja's father became very depressed. He was horrified by the Balkan war of the 1990s. At age fifteen, Sonja ran away to Berlin and became a punk because of ongoing conflict with her father. Sonja's father killed himself in 2015. He talked to Sonja on the telephone just a few minutes before committing suicide.

Sonja had been involved in anti-racist activism all her adult life. Her father's death propelled her to change her focus from anti-Semitic prejudice to anti-Gypsy racism. "I decided to concentrate on my roots." The first task was to do a lot of media monitoring. Sonja had developed these research techniques while working in Anti-Nazi, Anti-Semitic activism. "I found that when I was focused on Anti-Semitism there was a lot of interest and support. When I switched to Anti-Gypsyism, it was difficult to find anyone who wanted to help." Sonja examines German media portrayal of Sinti and Roma. "I have found numerous very negative articles and images which continue to be printed. The rise of right-wing groups has raised concerns of history repeating itself. Even individuals and organizations who are careful not to stereotype people of Jewish backgrounds, repeat racist stereotypes when discussing Sinti and Roma."

Sonja Kosche has given workshops at the Documentation and Cultural Centre for German Sinti and Roma, at RomnoKher Mannheim and at the Dokumentationszentrum, addressing the issue of anti-Gypsy hate speech

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Marcella Reinhardt née Herzenberger, is Chairperson of the Regional Association of German Sinti and Roma. She is married with two children, a son and a daughter, and two grandchildren ages four and seven. Marcella and her husband live in Augsburg, Germany.

"I am Sinti. My mother is Austrian Sinti and my father, from Stettin (Szczecin), Poland, is also Sinti. During the Nazi period many German Sinti went to Poland fleeing oppression."

"My parents were persecuted by the Nazis. My mother was in a concentration camp. During the Nazi period, Sinti and Roma children were not allowed to go to school." In the 1950s, the law was finally changed. By the time Marcella was born in 1968, Sinti and Roma children could attend school, but they faced tremendous discrimination.

Marcella began to work on the school accessibility issue while she was still a post-secondary student. The Landesverband Deutscher Sinti und Roma Bayern (Organization of Bavarian Sinti and Roma) helped her with organizational strategies. "There must be educational policies put in place to approach Sinti and Roma academic discrimination with clear historically accurate curricular lessons. It is essential that Sinti and Roma are open about their ethnic background so that mainstream society can come to grips with the extent of persistent stereotyping.

"In my former job I did not tell anyone that I was Sinti. I claimed that I was "Italian". Only recently have I come out about my identity. Even though I am the head of my association, I am still afraid of the Neo Nazi parties growing again here in Germany." After a recent TV interview, Marcella received negative feedback on social media. "My parents had to fight for recognition. I have to fight for recognition. How is possible that there is no definitive response from German society when Neo Nazism is returning in such strength? Why are German children not educated to eschew the horrors of racism toward all minorities?"

"Those who are alive today are responsible for their actions today. With the growth of Neo Nazi parties my work is even more timely".

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

"I have two tattoos. The one on my left arm symbolizes the development of a butterfly from a

chrysalis into a beautiful flying creature. The one on my back is a hummingbird symbolizing the

ability to find nectar in the centre of a flower."

When Alexander Diepold's eighteen-year old mother was in her 8th month of pregnancy, she

decided to take her own life. She was found by passersby, unconscious on a small street in the

town of Augsburg in Feb. 1962. A doctor delivered the baby and both mother and infant

survived. "That was the first sign that God was present and willed that I should live." Like his

older brother who was born when his mother was only fourteen, Alexander was taken away by

Child and Family Services and placed in a home for newborns. At two he moved to a children's

home run by Catholic nuns. "I was hyperactive. Sometimes the nuns would punish me by

locking me in a cupboard. I had to practice shallow breathing." At seven, Alexander left the

home and returned to his mother and her new partner who was a German policeman. "My

mother had to decide whether to give up me or my brother for adoption. The prospective

family chose my brother who was calmer and quieter. Adoption records were sealed, and did

not find my brother for almost fifty years."

Alexander never knew his birth father. His mother told him he was Italian to explain why

Alexander was the only dark one of all the siblings. "I believed her at the time." He only began

to learn about his family when he left the children's home at age seven. "My mother and I and

the other siblings all developed tuberculosis. I was hospitalized for thirteen months and only

attended school six hours per week. After I was reunited with my mother once again, her

partner became abusive and she escaped by moving the family to a Sinti encampment. The

accommodations were primitive, no electricity, no running water. I no longer attended school."

When Alexander was nine, his mother went back to the policeman. She told Child and Family

Services that Alexander was not her son. "I decided to leave and never return to live with my

mum." Alexander then went to a number of Catholic Children's Homes. "I met a nun who was

like an angel to me. Sister Ingfried. I stayed in contact with her until she died. She was my true

mother. Sister Ingfried recommended to Child and Family Services that Alexander attend the

Janusz Korzcak Children's Home. https://www.yadvashem.org/education/educationalmaterials/

learning-environment/janusz-korczak/korczak-bio.html

In 1974, several Catholic orders of nuns moved out of teaching and the German school system

took over the children's homes. Once again Alexander was thrown into chaos. The new

administrator, Siegbert Mueller, asked him – "how can I earn your trust? I understand your

hesitance. I need a chance to make it better." This was the first man Alexander felt he could

trust. Then the leader was moved, and Alexander had to start all over the process of learning

to trust. Alexander learned that Mueller was beginning a new school of his own and asked if he

could join him. Mueller waited several months before moving to give Alexander a chance to

petition Child and Family Services with the request to move schools. At first the request was

denied. Alexander went on a hunger strike, the authorities forced him to eat.

Alexander asked again how he could move schools. The bizarre answer was, only if you are

considered incorrigible. Alexander stopped going to school. His grades dropped. His report

card reflected the change. The Agency saw him as a risk. Mueller accepted him as promised

into his school. Alexander immediately reversed his course, raised his grades and completed

middle school. He then sat the exam to enter secondary school.

"I began secondary school in Aichach and in just three years, I finished secondary school with a

focus on economics. I thanked Mr. Mueller. I told him that my success was the result of his

unwavering support. "

Alexander had become a success story for the Child and Family Services. "I wanted to become

an educator for problem youth. I had clear ideas about what was good for these children and

what was not. I believed that first I must build their trust. Because I had come out of

childrens' homes myself, I believed I was the best person to work with these children. I

suggested to the German Educational authorities that I home school five troubled youth

between the ages of fourteen and eighteen." The government gave him that chance.

Concurrently, Alexander worked on preparatory courses to enter university. He went to school

full time and worked full time. After three years all five of Alexander's pupils were doing well.

They had finished school; were gainfully employed and not involved in crime.

By 1983, Alexander was licensed as a home school educator. He began to integrate the

troubled youth into regular public schools. Alexander's home school pupil load had now grown

to nine. Because the state education administration trusted him, students were moved from

other group homes to Alexander.

"I decided to improve my English by staying with a family in England for a several weeks. After

only a week there, I had a premonition that something had happened. My girlfriend and I

returned to Germany. I found a letter from a lawyer waiting for me. My mother had killed her

partner and was facing imprisonment." Alexander was now responsible for three younger

siblings. The University of Munich allowed him to complete his course work early citing special

circumstances.

In 1987, Alexander took over a dilapidated house in Augsburg which had been a former

children's home and registered it under the name The Madhouse. "At first the judge did not

want to approve the name, but I explained that the name, suggested by a student of mine

would house troubled youth."

Alexander married in 1988. "When my youngest sister's baby daughter was only two years old,

I received a call from the police. They asked me to identify two people who had been found

dead in a car. One was my sister and the other her boyfriend. We adopted the baby. She is

now thirty-two years old. My adopted daughter is the one who found my brother on Facebook.

"In 1993 I got my first Sinti pupils. There were eight of us on the team, but the Sinti boys only

trusted me. I learned that one of their mothers had serious drug problems. She wanted her

children back. I took custody of her three children so that the Agency would return her

children. Alexander worked with both the mother and the children. This was my first

engagement with Sinti students. I went to the municipal authority and said 'this woman is not

receiving a flat because she is a Gypsy." I need a flat immediately I told the counselor. I

received a flat.

An older Sinti woman told Alexander, "You are part of us." She said she had lived all over

Germany and Austria and she was sure I was Sinti. She told me, "Go to your mother, and ask her – Do you speak Romanes?" The next time Alexander visited his mother, he did just that. His mother turned white and asked "Who told you that? I don't want to talk about it." The older

woman told him that there is an area in Munich which was set aside for Sinti. Go to your

mother and ask her where she lived as a child. Ask your mother if she remembers a young

woman whose grandmother had lost her nose during the war. Alexander's mother told him

that she lived in Frauenholz. That was indeed the area where the Sinti had lived at that time

and his mother could remember the grandmother with the deformed face who lived there.

In 2016 Alexander began to trace his father's family through information provided by his

mother. She finally revealed that his father was German Sinti from the Lehmann family, one of

the seven clans.

Sinti from Munich came to ask for help with renting a flat, social assistance etc. Everyone said

you are one of us. But I did not want others to know because I was afraid that the Child and

Family Agency would no longer trust me because I am Sinti. I thought about it for two years,

then finally decided to come out as Sinti in 1997.

From that point on I have fought nonstop for equal participation of Sinti in mainstream German

society. I have a team of paid mediators of whom many are Sinti or Roma.

In 2012 a Memorial Site was constructed in Berlin to the memory the murdered Sinti and Roma

during the National Socialism Period. A new foundation was created by Sinti and Roma to build

education opportunities for Sinti and Roma students. Romeo Franz, now a representative of

the Green Party in the European Parliament headed up of the foundation from its inception.

This year, the foundation offered the position to me and I accepted. My goal is to promote

equitable conditions for Sinti and Roma throughout Europe.

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Joschi Rose was born in Heidelberg, Germany in 1970 and has always lived in that city. Joschi is chairman of the Bundesverband Deutscher Sinti und Roma (Federal Association of German Sinti and Roma) which he founded on the 27th of January 2017 in Heidelberg.

"Being born into a family which was then, and still is, so involved in the documentation and research of Sinti and Roma persecution and suffering through the Holocaust, has had a profound effect on my life. My early life was very influenced by my grandparents on my mother's side who also lived in Heidelberg. Listening to their stories of suffering and watching my father's efforts to achieve the historic acknowledgment by the German government of the Sinti and Roma peoples' persecution by the National Socialists during the Holocaust has been my greatest motivator in pursuing my job at the Documentation and Cultural Centre of German Sinti and Roma."

"My own experience of discrimination and prejudice growing up as a Sinti child and young man in Heidelberg has also influenced me deeply to work for a more tolerant future for all, but of course my greatest influence and hero has been and continues to be my father. My father, Romani Rose, inspired me to begin work at the Centre where I have immersed myself in all aspects of the Holocaust exhibition." http://www.sintiundroma.de/en/centre/about-us.html

"I feel it is very important to work on development aspects of the Centre. By interacting with the diverse visitor groups, I have gained a better understanding of how to improve the permanent exhibition and enhance its capability to deliver information about the Sinti and Roma people's struggle then and now, and their hope for a more tolerant future. While my main focus is the Holocaust exhibition, I am also involved in bringing other visiting exhibitions to the Centre. These changing exhibitions are also extremely important in creating a contemporary focus to attract people's attention to the main exhibition. "A recent exhibition, German Sinti Over Time-Acceptance, Dissent, and Cooperation, traces the Sinti from their arrival in Germany in the early 14th century through to the end of the 19th century."

https://zentralrat.sintiundroma.de/veranstaltungen/sinti-in-der-fruehen-neuzeit-akzeptanz-dissens-und-kooperation/

"In the future I would love to see the Centre improve on all fronts, attracting an ever-increasing, more diverse flow of visitors, by offering them an more informative state of the art documentary experience encompassing past history, present challenges and hopes for the future of the Sinti and Roma community. I believe that with these goals in mind the Sinti and Roma Documentation and Cultural Centre has an important part to play in creating a more tolerant and democratic Germany.

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Chairman: Central Council of German Sinti and Roma

Director: Documentation and Culture Centre of the German Sinti and Roma

Director: International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR)

The Sinti have been residents of Germany for at least six hundred years. German Sinti and Roma have served their country in the armed forces for centuries. Even during the Third Reich, Sinti and Roma served, mainly on the Eastern Front until banned on the basis of their ethnicity. Nonetheless, Sinti and Roma continue to struggle against discrimination perpetuated by media portrayals of a culture mired in poverty and lacking in human dignity.

"I was raised in the long shadow of National Socialism and the ruins of World War II. This shaped me in the context of this society. My grandparents were arrested, deported, and murdered in Auschwitz. My father went into hiding and survived. Survivor's guilt haunted him throughout his life. Ours had been a middle class traditional family. Before the war, we traveled from town to town, showing films throughout Germany. After the war, our family bought cinemas. I felt privileged because I could invite my school friends to the movies in our very own movie theatre."

During the 1960s, young people began asking their parents what their involvement had been during the period of National Socialism. "There began a realization of the complicity of ordinary German people in Nazi atrocities." University activists called on the government to democratize bureaucratic structures and to rid itself of former Nazis and Nazi sympathizers. The student uprising of 1968 fueled by the attempted assassination of student leader, Rudi Dutschke, "inspired me to take part in creating a more open and less racist German society."

Throughout Germany in the 1960s, there was a growing understanding of the spurious racial categories that had been devised by the National Socialists to legitimatize their genocidal practices. Awareness of the extent to which Jews had been exterminated in German occupied Europe gradually became widespread. However, the Sinti and Roma Holocaust was omitted from these disclosures despite the fact that German Sinti and Roma were consigned by the tens of thousands, to deportation and the gas chamber. Even those not sent to concentration camps were often forced to labour for the German war industry.

A permanent exhibit at the Documentation and Culture Centre of German Sinti and Roma in Heidelberg establishes "a memorial to our persecuted and murdered people." The history of persecution under the National Socialist government is traced "from the step-by-step deprivation of rights and exclusion from virtually all areas of public life through to state-organized genocide." (Ed. Petru, Gheorghe et. al. The Civil Rights Movement of the Sinti and Roma in Germany.)

"Nowadays no one in Europe would consider anti-Semitic hate speech acceptable, but hate speech against Sinti and Roma is rampant. The far right German National Democratic Party, launched a campaign in 2013 with the slogan 'money for granny, not for the Sinti and Roma' apparently alluding to allocation of social assistance funds." German law protects such slogans as 'free speech' as long as they do not call for specific actions against the targeted minority. The mainstream media does little to combat prejudice and discrimination. If an individual is accused of a criminal act, the media identifies the ethnic origin of the person along with the crime of which he or she is accused.

Continued pigeon holing by media shaped by negative stereotypes, leads some Sinti and Roma to deny their cultural identity. No one in Europe nowadays would discriminate against a person simply for being Jewish, but the same cannot be said for those whose origin is Sinti or Roma. This endemic racism creates an apparent conflict between cultural and national identity. "German Sinti are citizens of Germany; yet German composers of Sinti origin are viewed as cultural figures, not as national figures in the company of Beethoven or Offenbach." There is no inherent conflict between one's cultural and one's national identity, but cultural bias can create a disparity where none exists.

"Promoting and fostering social democracy throughout German society is the most important gift I have given to the German people and to Europe. An open democracy, which instills democratic values in its young people, is the best way forward for all Europeans regardless of their ethnic background." Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream that justice and equality for all would prevail; that one day our children "will live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character."

"I dream the same dream and will continue my work to advocate for human rights in the nation of Germany and throughout Europe."

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Alfred Ullrich was born in Schwabmünchen near Augsburg in 1948. "My parents met in a camp for displaced persons in Austria in 1945. My mother was from an Austrian Sinti family. My father was German from Sudetenland; I suspect he was in the SS."

My mother was the driving force of our family. She was born in Austria in 1916 at the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The entire Endress family of eighteen were picked up by the Nazis in 1939. Her first son, also called Alfred, died in the concentration camp with the rest of the family. Only one of my mother's brothers and two sisters survived, but they were never able to reconnect after the war. When my mother was released from Buchenwald in 1945 by American forces, she planned to return home to Vienna. However, she met and married my father. Their marriage lasted for two years. When they divorced my mother did return to Vienna. She went back to Bavaria several times, so that both my sisters were also born there. But in about 1953 we settled down for good again in Vienna. She eventually remarried an Austrian to get back her Austrian Citizenship. That marriage also did not work out.

"As a small child, I lived in a caravan frame with my mother and my sisters. Mother and the two girls lived in the main area of the caravan. I slept in the back where the hay would have been stored when the caravan was a functioning horse drawn wagon. The caravan frame is now my logo."

Alfred's mother was moved by the town of Vienna into a stone house in the centre of town. My mother had no choice but to move because her birth family no longer accepted her. "It was hard to leave the green and be surrounded by brick and walls. There was no indoor plumbing, no stairs joining the three upstairs rooms; just an iron balcony."

"My sisters and I began to attend school in town. The Sinti who travelled, attended itinerant schools, each day in a different village. We had more stability. One of my sisters learned book binding; the other became a seamstress. I did not like school and only completed eight years of regular education. I hitchhiked to Bavaria where I learned bronze casting. Then I went off to Germany and began to live like a hippie. In Munich and Berlin, I met many artists. These were the offspring of wealthy parents who could afford to travel around living a romantic life free of normal responsibilities."

During the Cold War, Soviet Bloc countries of Central and Eastern Europe signed the Warsaw Pact as a counterbalance to NATO. Conflicts were played out through proxy wars such as the Soviet led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Following this incursion, many Czech artists and intellectuals fled to West Germany. Alfred began working for a Czech artist as a free-lance printer. He moved into an old house in the county of Dachau where he could set up a copper printing press and create a copper print workshop.

In 1984, the artist association of Upper Bavaria accepted Alfred as a member. The association, Kuenstlervereinigung Dachau was opening its ranks to younger members at the time and Ullrich was recommended to them for his innovative etchings. "I worked both with and against the goals of the association. My Sinti background was always an unspoken presence in my reaction to actions of the Bavarian mainstream society. "Every day I would drive by the Dachau Memorial Site without giving it much thought. But by the 1990s, I began to reflect on what the memorial represented - the Dachau concentration camp which had once been there. Three of my uncles had been imprisoned at Dachau; only one survived. Some members of the artists' association wanted to focus on the accomplishments of the up and coming young artists, not revisit the Nazi past."

"In the late 1990s, after the fall of the wall, I met Barbara Scotch, a U.S. based human rights activist from the state of Vermont." Barbara alerted Alfred to protests occurring on the site of a former concentration camp in Léty, Czechoslovakia which had functioned as a concentration camp for Sinti and Roma during the Nazi period. Barbara and her friend, American born author Alan Levy, editor-in-chief of the Prague Post, 1991-2004, supported protesters' call for removal of a former commercial pig farm which now stood on the spot.

Alfred brought pearls from a necklace belonging to his sister and threw them at the door of the pig farm and into the flowers brought by protesters to honour the victims... symbolically "throwing pearls before swine. This was my first involvement in Sinti activism."

In 2006, my first exhibit appeared at the Neue Galerie in the town of Dachau. For this exhibit I build a simulated living room with couches and curtains and a TV showing an interview with my mother about the Buchenwald and Ravensbrueck Concentration Camps. Photos on the wall displayed a camping site known as the Landfahrerplatz Kein Gewerbe. Landfahrer is a synomym of Zigeuner, a derogatory term negated by Sinti. This stopping place for Sinti was established by the town of Dachau in 1947. It was a primitive accommodation with no indoor toilets and no potable water."

In 2008, I was invited to the Khamoro festival in Prague. I exhibited illustrations from a book by Mateo Maximoff The Ursitory (which had been translated in Czech) using only two colours-blue and red. The illustrations were dry point prints created by scratching images on metals rather than etching them.

From 2010 to the present, I have been deeply involved in Sinti activism. I have had several exhibits in mainstream galleries. In 2011, Ullrich's work was part of the Call the Witness Project at the Roma Pavilion of the Venice Beinnale.

https://callthewitness.net/Main

In 2019, Ullrich displayed a lithographic print at the FutuRoma pavilion of the 58th Venice Biennale as part of the concurrent events lineup. https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2019/collateral-events

My current exhibition at the Kai Dikhas gallery in Berlin, Sep-Nov 2019 features video stills of the Ottakringer Brauerei, a brewery in Vienna which was formerly owned by a Jewish family. The Nazis took over the brewery in 1939.

A second exhibit features monotypes - paper wetted and imprinted with the pattern of my mother's curtains in blue with the image fashioned onto the background.

"I feel much better now that I have come out about my Sinti roots. I have jumped over the Shadow."

Narrative by Mary Evelyn Porter

Roxanna-Lorraine Witt was born into a Sinti family of Holocaust survivors. Her mother's family lived in Minden, Germany where they were well integrated into the community. Her grandmother had five siblings, not all of whom survived the Holocaust. "My grandmother told me the real stories of the Holocaust. She told me about the cellar where the family would hide, where she could hear the SS walking overhead, about being afraid to breathe, for fear she might inhale too loudly and the family would be caught. She told me about seeing her mother beaten so badly that she lost a child she was expecting. My grandmother's family hid in the forest and shared a few pieces of bread among them that were provided by good-willed citizens, people who wanted to help them. My great grandfather was deported to Auschwitz, but somehow, he too survived, and the family was reunited after the war. We survived because we had people who would hide us as long as possible and provide us with some food, even though their support could have cost them their own lives."

Roxy´s grandfather's family were members of the railway workers' union; socialists who fought against the Nazis from the 1930s onward. "My grandfather was quite well educated. He taught my grandmother to read and write so that she could write him letters while he was traveling; thanks to my grandfather's tutoring, reading and writing became my grandmother's favorite hobby. My grandfather was a sailor, traveling around the world. When he finally settled down to be with her, my grandparents started a family of their own."

Roxy´s mother was born in 1970. Although the war had been over for thirty years, Nazi influence and ideology had not disappeared entirely. "Some of my mother's teachers were Nazis or the children of Nazis. My mother dropped out of school early, because the discrimination she had experienced in school made her decide to try and find a job rather than to continue with her education. Nonetheless my mother is knowledgeable and is fluent in three languages. Her goal has always been to give her children the chances she did not have."

In 1992 the Bosnia war broke out, and many Bosnians fled to Germany. "My father is Bosnian. I was born in 1993. My father returned to Bosnia before my birth and my mother had to raise me on her own. My mum also had the responsibility of caring for my half-sister, who is developmentally delayed. Additionally, she had to care for her parents, my grandfather had to take early retirement after his leg was amputated. He was then wheelchair bound. My grandmother had been severely traumatized by the Holocaust."

Roxy also experienced discrimination as a child. She was not invited to friends' birthday parties and some school mates called her a 'Gypsy'. School friends did not respond to invitations to Roxy´s parties either. "I was just a child and could not understand why I was being excluded. I thought it might have to do with us being poor. Hearing accounts from my grandmother about her traumatizing experiences during the Holocaust and from my mother about her experiences of discrimination, I understood the true reasons behind the exclusion. It seemed so surreal to me, because all my life I had identified myself as German – because Sinti are Germans. There is no discrepancy in that. Aware that the Sinti have been in the country for more than 600 years, there is no way a child can understand how he or she is "less German" because of being a Sinti."

Roxy enjoyed school and always achieved high marks. She was given academic ability testing and scored at the Gifted level. The school wanted to move her to a higher-level programme, but her mother was reluctant, "because the Nazis used to pick kids up from school and send them directly to the concentration camp, our people were afraid of never seeing their children again once they "let them go away", even all those years after the end of WWII. Even nowadays."

Secondary school was more racially mixed than her former school. It was there that Roxy began to hear the word ´Zigeuner´ repeated constantly. "My grandmother explained to me what the term meant; that it was a derogatory insult. At home the family never talked about what they had gone through during the Holocaust, but my grandmother warned me that the things the Nazis did to my people could happen again. She was the only family member to tell me about her fate and the fate of our ancestors. History can repeat itself."

Roxanna's best friend since primary school is ethnically German. Coincidentally, they have a lot of things in common, like the same last name. Although both families were unsure of their friendship at first, their strong bond opened a world of new impressions for everyone: "Our friendship helped to heal their lack of understanding. I believe our friendship helped to bridge an ethnic gap and bring understanding to an entire extended family. The acceptance and support I experienced in her family healed something inside me, inside my family, that had been broken generations ago. This was a very important experience in my childhood that contributed to me becoming who I am today and after more than 20 years, when we talk about our friendship back then, she says the same about me; how my family became hers and how it was so important to her."

At age fifteen, Roxy moved out of her mother's home. She decided to live on her own and work. Her ultimate goal was always to attend university. She spent a few years working on self -healing. At university, she studied marine biotechnology. Starting as a teenager, she also offered free tutoring to students in need and did a lot of voluntary work, especially in the political field. Her personal initiatives have included working with refugees, helping them to access education and learn German.

While she was at university, her biological father, who she regards as her "producer" sent her a Facebook friendship request. "I was afraid to respond, but he said, 'Don't worry I'm your father.' I discovered that I also have a brother and a sister from my father. My father abandoned them too, but I stay in touch with my half siblings." After introducing her siblings, he vanished from her life again. She never developed a bond with him or his origins, "His second wife, a Turkish woman who is the mother of my half-siblings, would later tell me how he would call my mother the "Zigeunerin" – the "Gypsy" when talking about her, as when the German authorities would send claims for child support which he never provided for any of his children. I realized how he had treated my mother as a sub-human because of her ethnicity. For this reason, I could never identify myself as Bosnian, I know how Sinti and Roma are regarded in Balkan countries. I am a Sinteza."

Roxy has worked for several large companies in the field of biotechnology. At the same time, she has worked with union movements and struggled against the exploitation of workers. Central to her belief system is the need to empower women. "I work with women to stress that education is power. The important factor in empowerment is to realize that there are far more similarities among ethnicities than differences. We need to build on those similarities to create a genuine global feminism."

Roxanna's uncle told her about the open position at the Documentation Centre for Sinti and Roma in Heidelberg. "I feel that I must work to bring education to the Sinti people, my people, because without education they will be prey to resurgence of the Neo Nazi parties. Among my family and my people, I am in a privileged position because of education and because my physical appearance allows me to hide my identity more easily if I wanted to, while there are a lot of our people who are unable to hide their identity. I need to share this privilege with others, so we become increasingly, well-educated Sinti and Roma people who are able to raise their voices against injustice and discrimination. We need to stand up for each other and stand together with other marginalized groups against those who threaten our very existence."

"I was raised to be a free human being. Once I recognized that truth, I was able to move out of the confines of racism. I believe that we must strive for the rights of all to be free human beings. Only in that manner can we erase inequality and injustice in this world. That is why I accepted the position of head of the educational section here at the Documentation Centre for Sinti and Roma."